Image Source: https://www.pressherald.com/2016/05/21/mariners-weigh-in-on-el-faro-weather-data/

Introduction

Seafarers face many hazards while at sea. The biggest of them all is undoubtedly the weather. It can often be severe and very dangerous. However, weather itself – as a hazard – cannot be eliminated. But it can be minimised through a combined process of (1) weather prediction from up-to-date forecasts and (2) weather avoidance as part of pre-voyage Passage Planning and (3) pro-active and 24/7 weather awareness and avoidance throughout the voyage. This Risk Bulletin takes a close look at this process and its utilisation by both Members and their Masters to ensure their vessels, cargoes and crews arrive safely at destination. It also looks at the ‘lessons learned’ from the tragic loss – during a 2015 Atlantic hurricane – of the containership ‘EL FARO’, together with all of her 33 crew.

Background

As advised by Lloyd’s List Intelligence Casualty Statistics, the cause of up to 50% of all vessels lost each year is due to ‘Foundering’ (commonly defined as ‘Sinking due to rough weather, leaks, breaking in two etc.’). This data confirms the view that severe and extreme weather present the greatest risk that ships, their owners and their crews face while at sea and even when in port. It therefore follows that the pro-active minimisation of the weather risk requires the greatest possible attention to ensure the successful exercise of both shipowner and crew due diligence.

Weather Forecasts and Passage Planning

MMIA Risk Bulletin 27, provides an outline and links to SOLAS regulation, IMO guidelines and industry best practice manuals on the subject of Passage Planning (PP). For vessels not regulated by SOLAS, PP must be accomplished to NCVS requirements.

Members and their Masters are reminded that IMO Res. A.893 (21) Guidelines for Voyage Planning provides:

‘All information relevant to the contemplated voyage or passage should be considered, inclusive of:

- Climatological, hydrographical, and oceanographic data as well as other appropriate meteorological information.

- Availability of services for weather routeing. (such as that contained in Volume D of the World Meteorological Organization’s Publication No. 9).‘

By way of clarification, MMIA believe that the aforesaid ‘information to be considered’ should include references to:

- UK HO/Admiralty, or equivalent, Pilot Chart Atlases and Sailing Directions (Pilot Books) in order to assess historical seasonal weather patterns and possible dangers during the course of the planned voyage.

- Pre-voyage weather forecasts, including long range forecasts.

- At least twice daily weather forecasts received during the course of the voyage from a GMDSS source.

- The use of supplementary Weather Routing assistance from computer-based Weather Routing software on board or the engagement of a professional shore-based Weather Routing service or a combination of both.

The information obligations and their application should be construed as being an integral part of all four of the SOLAS or NCVS required PP stages which include:

- Appraisal of all relevant information, inclusive of obtaining and reviewing all relevant seasonal weather and weather forecast data.

- Planning the intended voyage from berth to berth so as to avoid severe weather, inclusive of assessing alternative routes and identifying ports of refuge.

- Executing the plan, taking close account of observed weather conditions as well as forecast conditions, which may require prompt decision making and course deviation.

- Monitoring the vessel’s progress against the plan continuously.

Weather Routing Services

Weather Routing is a process which has evolved into a highly technical and sophisticated process over a period of many decades. It is now enhanced by real-time satellite data. Its underlying principals and goals are explained in the Introduction to Chap. 37, Weather Routing, of the current Nautical Almanac:

‘Ship weather routing develops an optimum track for ocean voyages based on forecasts of weather, sea conditions, and a ship’s individual characteristics for a particular transit. Within specified limits of weather and sea conditions, the term optimum is used to mean maximum safety and crew comfort, minimum fuel consumption, minimum time underway, or any desired combination of these factors.’

Members and their Masters are encouraged to read Chap. 37, Weather Routing, to gain a full appreciation of the process and the risk reduction benefits and fuel savings returns that third party weather routing can provide. This is particularly the case on longer voyages and in areas where seasonal typhoons and hurricanes occur e.g. the South China Sea and Bay of Bengal

Weather Forecast Transmission and Reception Systems

All commercial vessels over 300 GT engaged in international trade are obligated to comply with the SOLAS mandated Global Maritime Distress and Safety System (GMDSS). The GMDSS specifies the types of radio transmission and reception equipment and back-up systems which must be carried on board.

In general, the further a vessel trades from shore, the greater the transmission and reception range of the communications equipment she must carry. The GMDSS Sea Areas, the radio and satellite equipment required and the GMDSS Marine Safety Information (MSI) and weather broadcasts provided are as follows:

Area A1 –

- Navigation range between 20 to 50 n.mi. from shore, requires VHF radio only.

- Weather broadcasts by VHF Radio from national coast guard and met office stations.

Area A2 –

- Navigation range between 50 to 400 n.mi. from shore, requires VHF radio + Medium Frequency (MF) radio/NAVTEX.

- Weather broadcasts by VHF radio + MF text transmissions to NAVTEX receivers.

NOTE: NAVTEX receivers provide automatic reception and hardcopy print out of MSI, inclusive of weather warnings and forecasts. An explanatory article on NAVTEX and its use is available at: https://www.marineinsight.com/marine-navigation/navtex-on-ships/

Area A3 –

- Navigation range beyond 400 n.mi. from shore (‘deep sea’) between 70ºN. lat. to 70ºS. lat., requires VHF + MF + INMARSAT satellite connection.

- Weather broadcasts by VHF + MF/NAVTEX + INMARSAT C/SafetyNET (essentially a ‘deep sea’ version of NAVTEX).

NOTE: SafetyNET MSI broadcasts using INMARSAT C satellite transmissions are essentially a long-range version of NAVTEX MSI. More information and downloadable PDFs are available at:

https://www.inmarsat.com/en/solutions-services/maritime/solutions/safety/safetynet.html

Area A4 –

Navigation range above 70ºN. lat. to 70ºS. lat., (technically outside the range of INMARSAT) VHF + MF + High Frequency Single Sideband (HF/SSB).

Weather broadcasts by VHF + MF/NAVTEX +HF/SSB.

In addition to the above SOLAS mandated systems, Members and Masters can supplement the GMDSS weather forecasts provided by accessing internet weather sites. They may either be governmental sites (e.g. the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) site) which are free or commercial sites (e.g. Buoyweather or Windy) which may require payment of an access fee. Reception of available weather data and maps can be accomplished using a mobile phone, tablet or laptop.

NOTE: Members and their Masters need to understand that internet private weather sites are often designed primarily for private recreational activities, such as yachting and surfing. As such, these sites should always be used with caution by commercial vessels and then, only as a supplement to the SOLAS mandated GMDSS MSI reception equipment and the weather forecast information these systems provide.

Times and Details of GMDSS Weather Reports

Information is available in Volume D of the World Meteorological Organization’s Publication No. 9.

More detailed information, which is updated regularly by UK Notices to Mariners, is available from the UK Hydrographic Office’s six volume publication ‘Admiralty List of Radio Signals’ (ALRS). GMDSS weather forecast information is provided by Volume 3 (NP283) – Maritime Safety Information Services (Parts 1 & 2) which covers:

- Maritime Weather Services

- Safety Information broadcasts

- Worldwide NAVTEX and SafetyNET information

- Radio-Facsimile Stations, frequencies and weather map areas

NOTE: In order to meet SOLAS mandated obligations, vessels engaged in international trade must carry a full and updated hard copy and original set of the ALRS (or an approved alternative) or have shipboard access to an approved electronic version. Vessels engaged in domestic trade must carry or provide shipboard access to similar information as specified by national flag NCVS regulation.

Weather Avoidance and the Loss of the ‘EL FARO’

The US National Transport Board (NTSB) report on the loss of the ‘El Faro’ and her 33-man crew provides some tragic lessons on weather awareness and ‘life and death’ situations at sea. The report runs to 300 pages. It includes many of the bridge conversations between the bridge officers and crew and remarks made by the Master which were recorded by the ship’s VDR ‘black box’.

The ‘EL Faro’ was a container ship which flew the US flag. She was engaged in a weekly roundtrip container and Ro-Ro liner service between Jacksonville, Florida, and San Juan, Puerto Rico. The vessel was 40 years old but Classed by ABS and subject to US Coast Guard inspection.

The ‘El Faro’ and her sistership were soon to be replaced in the trade by two new LNG powered vessels. The ‘El Faro’s Master was concerned that he would not be appointed to one of the new vessels as his performance reports had not been entirely satisfactory. He was therefore under pressure and facing redundancy.

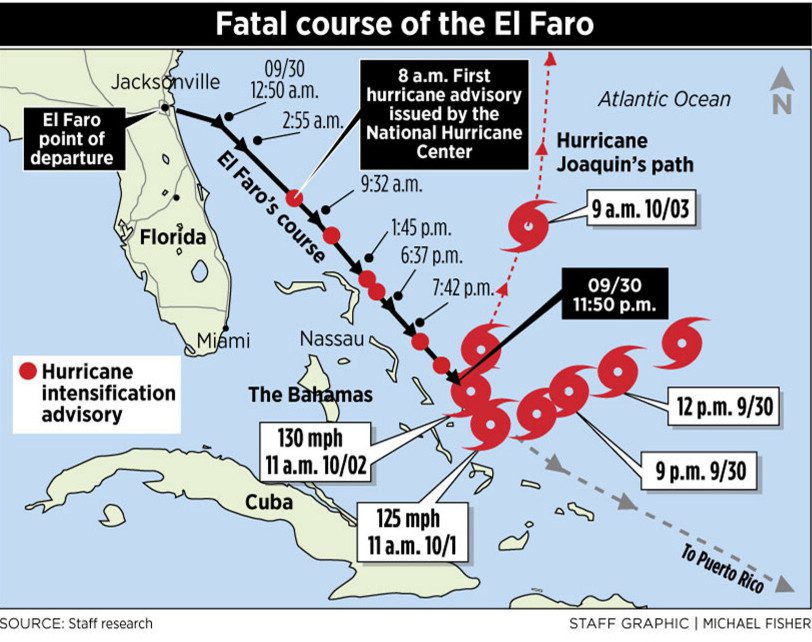

The ‘El Faro’ loaded cargo at the port of Jacksonville, Florida, on the 28 and 29 Sept 2015. Late in the evening of 28 Sept, the US National Hurricane Centre issued warning that a tropical depression had deepened to a tropical storm about 400 n. mi. NE of the Bahamas. The 2nd Mate texted the Master to advise him of this report, the next morning, 29 Sept., at about 0800 hrs.

At about 1700 hrs, and about three hours before completion of loading, the Hurricane Centre advised that the depression had been designated Hurricane Joaquin.

NOTE: The Hurricane Centre advice was received through the INMARSAT C system and was displayed directly on the bridge.

At 1831, the 2nd Mate sent a text enquiry to the Master: “What’s your plan?” The Master’s reply was to “steam our normal direct route” to San Juan and, according to his assessments of the forecasts, Joaquin would “remain North of us.”

NOTE: The vessel was provided with shipboard access to a private and computer based weather display programme known as the Bon Voyage System (BVS). E-mail updates were transmitted regularly to the Master’s computer terminal located in his office. The intended process was that the Master would download the updates and then forward them to the bridge computer.

At 1909, the 2nd Mate responded that, if necessary, “we have [alternative] routes” through Mayaguana, Crooked Island, and Northeast Providence Channel, referring to passages through the Bahamas that are long-established routes for avoiding storms. The Master did not reply.

At 2007, the ‘El Faro’ departed from Jacksonville. Before disembarking, the pilot spoke with the Master about the approaching hurricane and plans for avoidance. The Master’s reported reply was, “We’re just going to go out and shoot [go south] under it.” The pilot later reported to the NTSB inquiry board that no one on the ship’s bridge reacted to the Master’s stated intention.

Weather reports continued to be received during the night and into the morning of 30 Sept. The advice was that the hurricane was increasing in intensity and was tracking WSW – towards the ‘El Faro’s 133º direct course line to San Juan – with winds of 60 knots, gusting to 75 knots. At about 0630, the Master and Chief Officer plotted all of this information and then altered course slightly southwards from 133º T. to 140º T. so as to go further South and increase the vessel’s closest point of approach (CPA) distance to the hurricane centre.

At 1147, the 2nd Mate went to the bridge to relieve the 3rd Mate and take the 12-4 morning watch. An exchange between these two officers reveals that the 2nd Mate was concerned about the Master’s decision to proceed along the vessel’s ‘normal track’.

“He’s [the Captain’s] telling everybody [the crew] down there—ohhh, it’s not a bad storm, it’s not so bad . . . it’s not even that windy out . . . seen worse.” Minutes later, the 2nd Mate added, “I think he’s just trying to play it down because he realizes we shouldn’t have come this way . . . saving face.”

The NTSB report provides the details of the further conversations between the watch officers and with the AB lookouts on their watch. As the hurricane intensified and continued to move closer towards the ‘El Faro’, the crew’s concerns also intensified, and questions were voiced as to why the Master had not ordered a diversion to a safer route. Despite this, the Master’s orders to stay on track were not directly challenged at any time.

This situation continued throughout the day of 30 Sept. Hurricane reports were broadcast from the Hurricane Centre using INMARSAT C/SafetyNET but not all of them were recorded as being received on board the ‘EL Faro’. The Master sent the usual noon position report to owners and advised that, with respect to the hurricane, ‘precautions were being taken’. It is notable that the hurricane wind speeds reported to owners were significantly less than the speeds advised by the Hurricane Centre.

NOTE: During the course of the inquiry conducted by the US Coast Guard, BVS officials admitted that some of the data contained on the BVS had been up to 10 hrs. late. Further, Hurricane Centre officials also admitted that some of the data that they transmitted contained errors.

At 2305, the 3rd Mate called the Master by bridge telephone to suggest that he might want to look at the latest forecast. He told the Master that maximum winds were 100 mph (87 knots) at the storm centre and that the hurricane was moving toward 230° at 5 knots: “It’s advancing toward our trackline and . . . puts us real close to it . . . we’re looking [to] meet it at say like four o’clock in the morning.”

The Master did not go to the bridge, and he declined the 3rd Mate’s telephone suggestion to alter course further to the South to put more distance between the hurricane and ‘El Faro’.

At 2345, the 2nd Mate arrived on the bridge to relieve the 3rd Mate. They discussed their concerns about the weather and diversion to alternate routes. However, following the Master’s orders, the 2nd Mate continued on track.

At 0409 on 1 Oct., the Master arrived on the bridge. Unbelievably, he announced that he had “Slept like a baby.” Shortly afterwards, a succession of events on board the ‘El Faro’ took place that were to spell disaster.

By this time, the course had been altered to 116º in an effort to run directly away from the hurricane and put more distance between the ‘El Faro’ and the hurricane’s centre. This change of course created a large wind heel which, in turn, caused a serious problem with the main engine’s lubrication system. In addition, water was reported to be flooding into No. 3 hold due to an access scuttle which had evidently not been properly closed and ingress from a fire main broken by improperly secured cargo.

The situation rapidly deteriorated with the main engine stopped and the vessel sinking and going down by the head. A full appreciation of the dramatic events which then occurred can only be obtained by reading the NTSB report. However, in brief, the situation could not be controlled and, after transmitting an emergency message through the GMDSS system, the Master ordered abandon ship at 0729. His instructions were to launch and get on board the vessel’s life rafts.

At 0739, the VDR audio recording ended. Hurricane Centre data shows that, at this time, the hurricane centre – with winds gusting to 120 knots – was located 17 n.mi. from the position of the ‘El Faro’s’ sinking. There were no survivors, and no bodies were ever recovered.

NTSB’s assessment as to ‘Probable Cause’

As stated in the NTSB report:

‘…the probable cause of the sinking of El Faro and the subsequent loss of life was the captain’s insufficient action to avoid Hurricane Joaquin, his failure to use the most current weather information, and his late decision to muster the crew. Contributing to the sinking was ineffective bridge resource management on board El Faro, which included the captain’s failure to adequately consider officers’ suggestions. Also contributing to the sinking was the inadequacy of both TOTE’s [the shipowners] oversight and its safety management system.’

Conclusion and Takeaway

The message provided by the loss of the ‘El Faro’ seems clear: ‘Ignore weather warnings and their proper application to pre-voyage PP and, as necessary, PP adjustment during the voyage, at your peril.’

But why did the ‘El Faro’s’ Master act in such an unprofessional and dangerous manner? Indications are that he was concerned about losing his job and that he wanted to impress owners with his ability to keep his ship to a tight trading schedule, despite the presence of hurricane weather. The disastrous result was the loss of his vessel and the death of his entire crew.

Members should also note that the owners of the ‘El Faro’ were also heavily criticised for the inadequacy of the vessel’s SMS and its implementation as well as their failure to pay proper attention to their master’s dangerous navigational decisions.

MMIA encourages all Members to ensure that a copy of this Risk Bulletin is provided to all of their Masters, DPAs and Ship Managers. Further, that the critical message it conveys is understood and, importantly, is acted upon.