You Only Get One Chance, So Get It Right!

The transfer of the conduct (‘the con’) of a vessel from the Master to a Pilot remains a mysterious exercise to most non-seafarers. Regrettably, despite clear IMO Res. A.960 (23) guidance on how this critically important process is to be safely accomplished, it still appears to be a mystery to many Shipmasters and Pilots as well. The results of an inadequate transfer and the consequent destruction of jetty container cranes by the containership “CMA CGM Centaurus” at Jeb Ali, UAE, are illustrated by the above photo as contained in a recently released MAIB report.

By way of background, the use of a ship’s Pilot to assist with the navigation in and out of ports and their berthing and unberthing is now compulsory in most places. The underlying safety rationale is that a Pilot and the tugs he controls provide the benefit of local knowledge and ship manoeuvring expertise. All quite logical. But what happens if the Pilot is not as competent as he should be in a world where there is now a shortage of such people?

Apart from Panama Canal pilotage, the accepted law on the point is that a Pilot is deemed to be the employee of the shipowner when he steps on board. As such, he acts in an assisting capacity only – which normally includes taking the con to give helm and engine orders – but the Pilot never assumes command. The Master therefore always bears ultimate responsibility and he is obligated to take back the con if he observes that the Pilot’s orders are likely to place the vessel in danger. Easy in theory but challenging in an emergency scenario when overriding the Pilot’s con of the vessel might make the situation even worse.

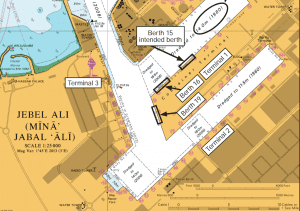

The circumstances of the “Centaurus” incident were that the Pilot boarded the heavily laden containership as she entered the Jeb Ali port channel. Arriving on the bridge the Pilot ordered “Full Ahead” on the main engine (which increased ship’s speed to 13.4 knots) and bid the master a cheery, “Welcome to Jeb Ali”. The Pilot then announced that two tugs would be engaged and the ship would be berthed at Terminal 1. He also asked the Master whether the ship was ‘good [at] turning’ with the Master replying that, “She is, but maybe she’s heavy”.

The Master/Pilot exchange was totally inadequate and not in compliance with IMO Res. A.960 (23) or ICS published guidelines. Nor did it comply with CMA CGM’s navigation and pilotage procedures as incorporated into the ship’s manual. As a consequence, there was no confirmation of the roles of the full Bridge Team, inclusive of acquiring and sharing navigational information with the Pilot.

Instead, the Pilot took not only just ‘the con’ of the vessel but also complete control of her navigation with the Bridge Team acting as little more than bystanders. Thus, when he later attempted a 90º turn to port (at a relatively high speed of 7 knots) into the designated berth basin, neither the Master nor any other member of the Bridge Team were capable of challenging the Pilot’s decision or timing.

Quickly realising that he had started the turn too late and at too high a speed, the Pilot made frantic attempts to recover using the helm, main engine and the two tugs under his control. Too little, too late.

As captured on Video, the bow of the “Centaurus” struck the jetty causing severe damage to the ship’s hull, the complete destruction of a jetty container crane and damage to another. Ten shore personnel were injured, one of them seriously. Claims for hull repairs, crane repairs and a complete replacement, as well as extensive downtime and loss of earnings for both parties, cost tens of millions of dollars.

CONCLUSION AND TAKEAWAY

The MAIB’s full report is carefully documented and illustrated but is not permitted to find fault or apportion blame. However, the reasonable inference must be that both the Pilot and the Master were negligent in failing to comply with IMO Res A.960 (23) Annex 2 and the ICS publication, Bridge Procedures Guide (5th Ed). The Master was also negligent in not complying with CMA CGM’s stipulated Master/Pilot exchange procedures. If these guidelines and procedures had been followed, so that the Pilot, Master and OOW were enabled to work together as a co-ordinated Bridge Team, then the likelihood is that this very costly incident would not have occurred.

Maritime Mutual would like its Members to encourage their Ship Managers, Masters and Crews to benefit from the unfortunate lessons provided by the “Centaurus” incident. Please forward this Risk Bulletin and the links it contains to your Managers, Masters and all of the vessels in your fleet. Ask them to think carefully about their ship’s SMS manual Master/Pilot exchange procedures. Are they sufficient to ensure full compliance? How they are implemented when a Pilot comes on board? Critically, are they really effective? Or just another tick box exercise? The answers and pro-active assessment and re-enforcement could save you a lot of time, stress and money.