Introduction

Members who trade their vessels through the Singapore Straits will know the three letter anacronym ‘OPL’ stands for ‘Outside Port Limits’. What may not be known are the serious risks and penalties which can arise if vessels are ordered to anchor or idle in OPL areas to wait for voyage orders, conduct ship-to-ship (STS) cargo operations or take on stores and make crew changes. This Risk Bulletin discusses the legal risks and practical realities of using the so-called OPL areas for operational purposes with the intention of avoiding inside port limits fees and regulations.

Background

The Malacca and Singapore Straits are bordered by the nation states of Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore (the littoral states), all of which have ratified the UN Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS). These states all recognise and accept the UNCLOS designation of ‘territorial seas’ as extending to 12 n. mi. from a state’s UNCLOS defined base line. Importantly, they also recognise the UNCLOS designation of ‘archipelagic seas’ as it applies to Indonesia which extends Indonesia’s territorial seas limits and control to well beyond 12 n. mi.

Within the above noted territorial or archipelagic seas or waters areas, each of the three littoral states is entitled to exercise sovereignty except over the exercise of ‘freedom of navigation’ or ‘innocent passage’ (as provided by UNCLOS Art. 17) by all vessels transiting these areas. However, all such passages must be ‘continuous and expeditious’ (UNCLOS Art. 18.2). For practical purposes, this means a transiting vessel should not stop or anchor unless it is effectively forced to do so for reasons of its own safety, danger or distress or to render assistance to another vessel in distress.

An example of a forced stop would be if a vessel suffered an engine failure and needed to anchor for a short period to accomplish repairs. However, it would not include stopping or anchoring in territorial or archipelagic seas areas to wait for orders, conduct STS operations or take stores and affect crew changes without the prior permission of the state having the legitimate sovereign control of that area.

Regrettably, the littoral states have not yet all agreed as to precisely how the overlapping areas between their respective territorial and archipelagic seas limits are to be recognised and enforced as between themselves as well as against any vessel transiting those waters. Negotiations continue and formal agreements and published national laws and amendments have followed. Meantime, numerous and complex boundary uncertainties remain in the Singapore Straits which have frequently placed shipowners and mariners in difficult and costly situations.

NOTE: An interesting article, ‘Drawing Malaysia’s Line Over the Straits’, provides the history of the aforesaid boundary agreements and their ongoing but slow-moving resolution.

Vessel Detentions and Fines in Malaysian Territorial Waters

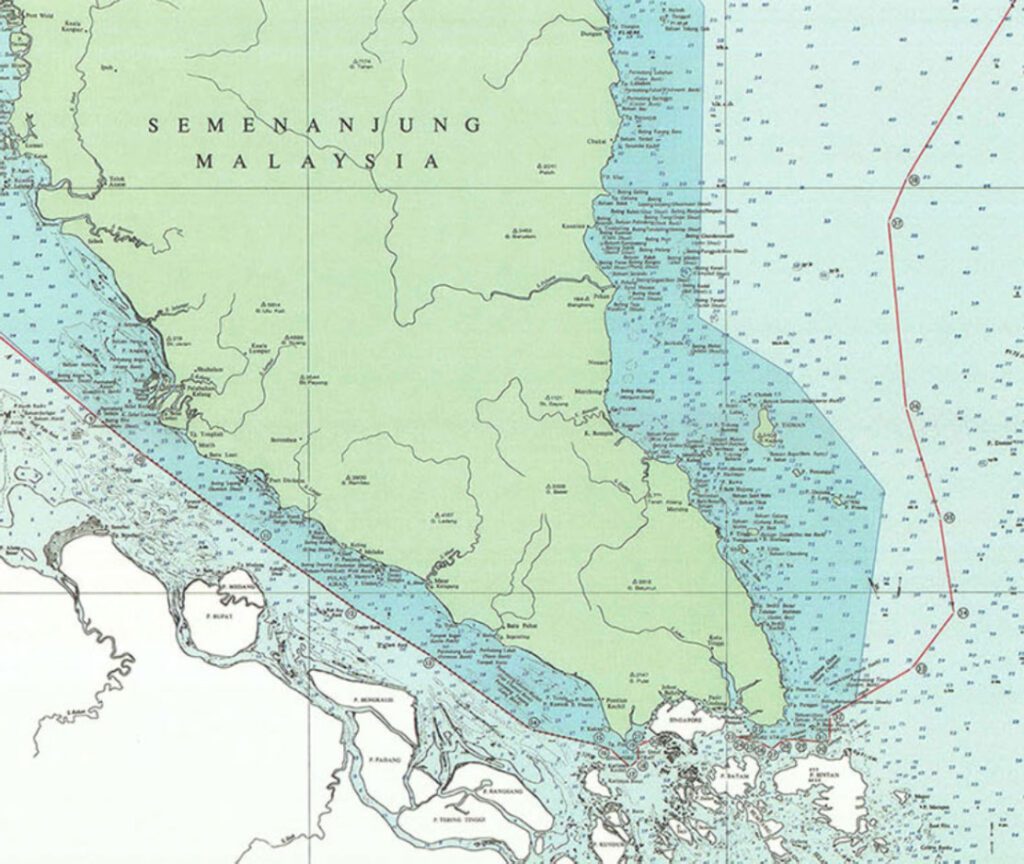

The image above is for illustrative purposes only and has been extracted from Malaysia’s 1979 Territorial Waters Chart. Members and their masters should obtain a full size and original copy of the above referenced chart from their chart agent.

The darker blue areas depict the outer limit of Malaysia’s territorial waters, which – due to the base line being extended by Malaysia to include offshore islands – can be located up to 60 n. mi. from its main coastline.

NOTE: The red line depicts Malaysia’s declared Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) which is not directly relevant to this Risk Bulletin

Malaysia’s Territorial Sea Act 2012 is enforced by the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA) and the Malaysian Marine Department. As a part of this enforcement, the Malaysian Merchant Shipping Ordinance (MSO) 1952, S. 491B (1) obligates all vessels to notify the Malaysian Director of Marine when entering Malaysian territorial waters to conduct activities which include cargo tank cleaning, ship-to-ship activity, vessel lay-up, welding and other hot work, anchoring in an undefined anchorage area and conducting any form of underwater operations. If this is not done, a criminal offence will have been committed.

NOTE: The obligations set out in the MSO have been promulgated to all mariners by Malaysian Notice to Mariners 5/2104.

The OPL area situated to the immediate south of the Johor Port Limits is usually referred to as the East Johor OPL or Eastern OPL. A significant number of detentions by MMEA officers of non-reporting vessels found in this area have taken place over the past few years. Vessel detentions are also reported to have occurred for the alleged non-payment of Malaysian light dues.

Delays of between 1-3 days will also be suffered as it is usual for the Master be escorted ashore for questioning. Subsequent prosecution will then take place before a local magistrate. The court imposed fines for each offence range from between MYR 50,000 and MYR 100,000 (approx. USD 12,000 to USD 24,000.00).

Vessel Detentions and Fines in Indonesian Territorial and Archipelagic Waters

The image above is for illustrative purposes only and has been extracted from Map 1 in the US Govt. document ‘Limits of the Seas, No. 141, Indonesia, Archipelagic and Other Maritime Claims and Boundaries’. Labels and arrows have been added to show Singapore, Bintan Island in Indonesia and the ‘OPL or Not OPL’ area commonly referred to as the East Johor OPL.

Indonesia’s territorial and archipelagic waters were established by reference to UNCLOS Art. 46 and are listed as base line points and segments in Indonesian Government Regulation No. 38 of 2002, as amended by Reg. No. 37 of 2008. The red dots depict the archipelagic waters base line points which are joined together by short base lines. Indonesia is entitled to exercise full sovereignty within this area.

NOTE: The solid purple line shows the currently agreed seabed rights boundary between Malaysia and Indonesia. Each country is entitled to exercise ‘sovereign rights’ (which are less than provided by full sovereignty) over their respective seabed areas.

Regrettably, it has not been possible to locate a map or chart which shows both the Malaysian territorial sea and Indonesian archipelagic sea limits and any overlaps which may or may not exist between them. However, Indonesian naval vessels have conducted a large number of commercial vessel and shipmaster detentions in the so-called East Johor OPL area north of Bintan Island. The assertion being that the detained vessels were anchored or idling and/or were engaged in STS operations in Indonesian territorial waters without formal permission to do so.

If a vessel is detained, the Master will be escorted ashore for questioning and the implementation of criminal proceedings. Reports are that this process and the payment of resultant court fines of up to about USD 20,000.00 and vessel and Master release can take up to eight months. Disturbingly, there are also allegations that very large cash payments (up to USD 300,000.00) have been demanded to facilitate the quick release of the vessel and Master.

Conclusion and Takeaway

The principal message to Members is that the term ‘Outside Port Limits’ does not mean ‘Outside Territorial and/or Archipelagic Waters’ and outside the exercise of full sovereignty and control by the designated littoral state. In short, ‘OPL’ does not mean ‘International Waters’, despite being evidently misinterpreted as such for several decades.

Another important message is that UNCLOS and the territorial and archipelagic waters and other boundaries it defines is subject to the interpretation of the ratifying states, their national law implementation and their cooperation with other coastal states. Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia continue to negotiate and cooperate, but complex and contentious boundary uncertainties still exist.

MM’s risk management recommendations to Members are as follows:

- Access to a copy of this Risk Bulletin should be provided to your ship managers, DPAs and all Masters of ships navigating in the Singapore Straits.

- Masters should, as part of their STCW Code Passage Planning obligation, ensure that:

- They check all paper and electronic charts being used to ensure that territorial and archipelagic seas limits and baselines are marked and fully understood by all bridge watch officers as being able to be extended well beyond 12 n, mi. from a charted coastline.

- They access copies of all relevant Notices to Mariners promulgated by the Malaysian, Singaporean and Indonesian Maritime Authorities.

- Members should not enter into any agreements with charterers or other parties to utilise so-called OPL areas to anchor or idle while waiting for orders or conduct any STS or bunkering operations without first ensuring that a local agent has been appointed and formal written permission with a designated anchorage area has been granted by the appropriate maritime authority.

- Finally, as to the question ‘OPL or Not OPL?’, it appears that the term ‘OPL’ has been seriously misinterpreted and misused. As such, the use of this term to suggest an entitlement to engage in unregulated operations without port or maritime authority permission or payment of fees is simply wrong and should be firmly resisted.